Pandemic Past and Present: Tidtaya Sinutoke

Thai musical theater composer on life as an artist in America, taking artistic leaps during Covid, and rehearsing across continents

I first interviewed Thai musical theater composer Tidtaya Sinutoke in March of 2020, just when lockdowns began around the world. I was in Thailand, she in the US. It was an email interview for the Bangkok Post. People hadn’t really started using Zoom yet. I didn’t even think about a video call. And with such a big time difference between us, an email interview made the most sense. I interviewed her along with her collaborator, Isabella Dawis, a Filipina-American performer and playwright. They were both working on their musical Half the Sky, about a young Thai woman setting out to fulfill her dream to summit the Everest after a death in her family. In the months and years following, I would continue to receive updates in my inbox about their musical theater projects.

This time, I tried to get an interview with Tidtaya while I was in Germany. It would be easier for both of us when we’re just six time zones away from each other. But it turned out that Tidtaya would be in Bangkok to visit her family. Even better. I would get to meet her and do the interview in person.

Tidtaya was already sitting in front of our meeting place, a restaurant at a community mall near her sister’s place in Bangkok, when I arrived. She wore a face mask but removed it to say hello. Tall but slightly slouching, she was soft-spoken and shy at first, her voice often fading into barely audible whispers at the end of her sentences. But her voice gained strength and confidence when she dove into the details of her projects and reflected on her life and career as a musical theater composer in New York City.

Tidtaya’s music education began with the piano. She sang in a choir. She majored in flute at Mahidol University’s College of Music’s pre-college program in Thailand. There, she didn’t devote herself to only one instrument. “I was the weird one who took piano lessons, composition class, and voice lessons.”

There weren’t and still aren’t many musical theater productions to see in Thailand. It’s no surprise that Tidtaya saw her first musical and fell in love with it during her senior year of high school in the US. It wasn’t Broadway or anywhere near New York or other major cities. She was attending a public school in Saginaw, Michigan, and tagged along her host family and their children to see a production of Grease in Ohio. “Do I like Grease now? Not really. It’s not my favorite musical, but there’s something about musicals that’s quite magical.”

Tidtaya went to Berklee College of Music in Boston for her undergraduate studies. Since the school didn’t offer a degree in musical theater, the closest she felt she could get to it was by majoring in professional music, thinking she would become an arranger. In her last year there, she saw a poster advertising a master’s degree program in musical theater at NYU Tisch School of the Arts. Tidtaya arrived at NYU not having written a single musical, unlike most of her classmates. But she figured it out soon enough and graduated in 2013.

Today, she has seven musical theater projects in development. During the interview, Tidtaya often described herself as “lucky”. She has won numerous grants, fellowships, and residencies to develop her musical theater projects since her graduation from NYU. None of her musicals have been made into a full-scale production yet, but she seems to be happily working on them with other artists, discovering new talents to work with across America along the way.

She got even busier during Covid. Tidtaya seems to be one of those artists who weren’t just lucky to be able to still work as artists during the pandemic, but also had a creatively fruitful and exploratory time. The period also saw her occasionally returning home to Thailand and making theater happen continents away with her colleagues who were scattered across the US. We talked about her struggles and breakthroughs, her loneliness and longings during the pandemic, and her sense of achievement as an artist. Along the way, she gave glimpses into what it’s like to be a Thai artist in America and into the New York and regional theater scenes before, during, and after Covid.

The interview has been condensed and edited.

When I interviewed you in March 2020, you said then that it had been a lonely career as the only Thai musical theater composer in America. That was the beginning of Covid. Did that sense of professional loneliness persist during Covid?

Yeah, a little bit. But finally, there’s another Thai student at NYU. She’s a words person, but still, it was nice. She actually reached out to me during the pandemic as she was applying for schools and asking my opinion. It’s really nice because when I started my grad school, I had a really great mentor. She’s Australian, NYC-based, and a fellow composer like me. She came to most of my readings, and still does even now. Once in a while, I would ask her questions about agents and contracts, and she would still reply.

And this mentor, where did you meet her?

The school paired me up […] But it’s nice to become a mentor to this Thai student without the school pairing. She’s finishing her last semester this month.

You said in the interview that you were lucky to still have your job when the first lockdown began in the US and all over the world, while for many people around you shows were cancelled or postponed. Some people lost their income. What was the atmosphere like for you in New York during the first year of Covid?

I was one of the lucky ones.

What job did you have then?

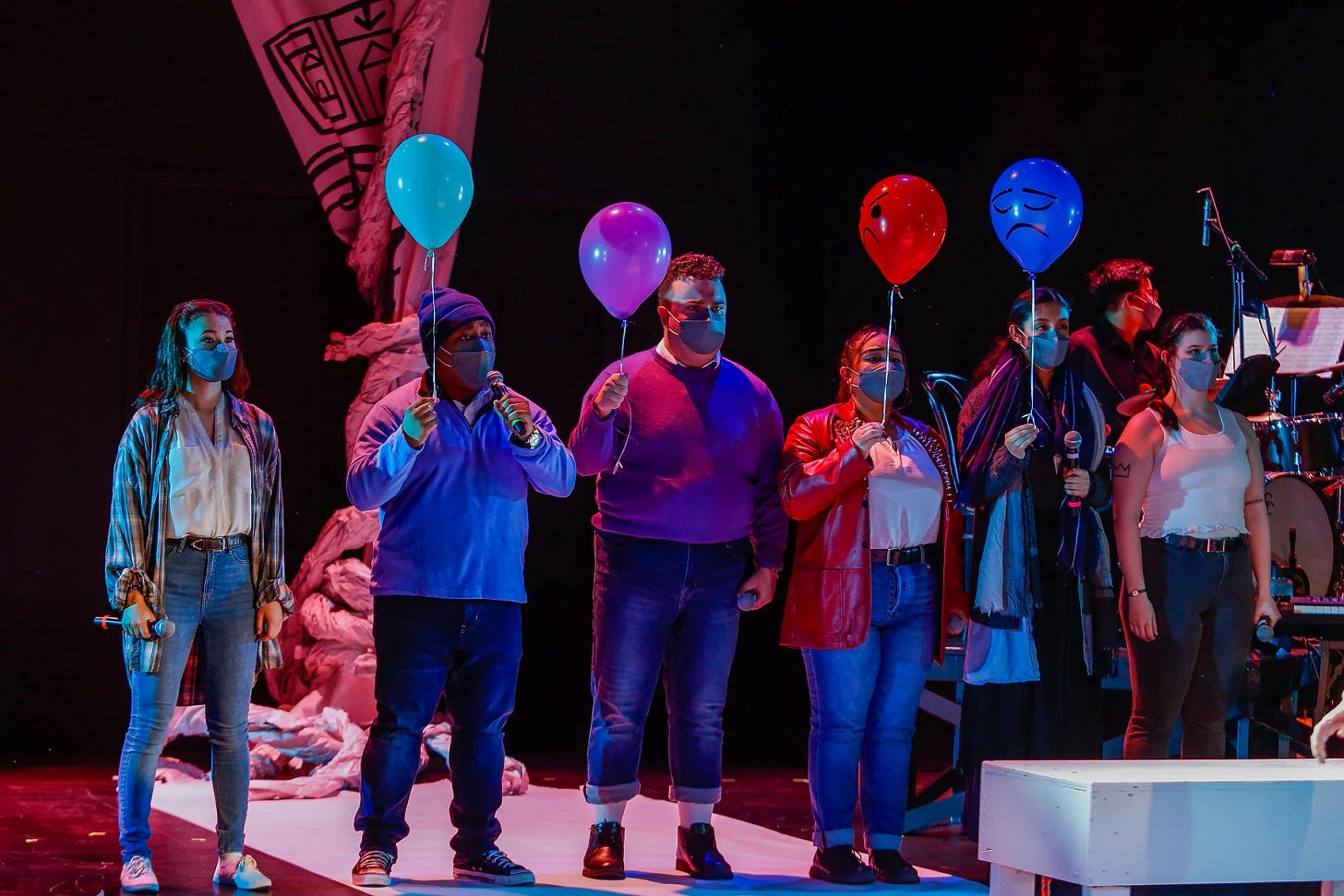

I won the [Billie Burke] Ziegfeld Award for women composers of musical theater. We were talking about Half the Sky, and that was the year all the theaters were shut down. The Fifth Avenue Theater was shifting towards radio musicals, so I felt like it was a strange time for everyone, but I was one of the lucky ones who got to do fellowships and got to have all these opportunities. I got my first production during the pandemic. I also came back to Thailand, and that was fall 2020 when the vaccine wasn’t available for anyone who weren’t essential workers. This sounds crazy. Isabella lived in Minnesota at the time. Our director lived in California. I was in Thailand. Most of the actors were in New York. And so the theater hired a recording studio that had seven rooms for everyone to be in [separately]. They all tested before coming into the room. We had a virtual rehearsal two weeks before that. It was a crazy time. That was December 2020, and that was when the second wave of Covid happened in New York. There were discussions that in the worst-case scenario, they would mail everyone a microphone. And then my music director also had to fly to Seattle to record musicians there. He had Covid right before going there, so he was immune enough to go. I mean thinking back, I just remember having weekly production meetings at 3 AM in Thailand, and whenever we did recordings, it was in New York. That’s 10 PM to 6 AM, and I had to deal with notes. And in Seattle, that’s midnight to 10 AM. So it was a lot of not sleeping.

So it became more intense because everyone was everywhere?

It was very intense. And we still had to rewrite and everything. I think the beauty of writing with a partner is to be in the same room and create things together, which we couldn’t have, obviously.

How did that feel?

It felt strange. And I felt we worked better in the same room. With the recording with the musicians, we had a Tibetan [musician] coming in. That was eye-opening for me because that’s when we collaborated with someone who doesn’t read Western musical notation. And luckily, we had a music director who helped us along. Actually, the best way to do was to play the song and asked him to improvise. It was an interesting method to deal with. That was what I remember with the pandemic. It’s like we were still doing theater. And in 2021, we won the Fred Ebb Award. Theater opened in fall 2021 or summer 2021? But they still looked at your vaccination cards. It kinda opened, but it was not 100 percent open.

What kind of place were you in creatively during the first year?

It’s so weird to say it out loud, but it was like “exploring”. I’ve been training as a musician for most of my life. I started off with playing the piano […] In 2017, two months after I won the [Jonathan] Larson grant, I found out that my mom had cancer. I wrote something back then. It was like a monologue, some piano accompaniment, and some melody. And I sent it to my friends, like, “Can we write a song based on this monologue?” So [Dear Mr. C] started in 2017, but I didn’t know what it was. It felt like a therapy session in a way. In 2020, I joined a writers’ group, and I kinda looked back at all the fragments of the songs that I wrote in 2017, and I started writing a book for the show and finished that in 2021.

New York City in 2021 had a grant for 5,000 dollars. It was to welcome back the performing arts world. So I [proposed] this project, and I got [the grant]. You know sometimes when you get something with a deadline, you force yourself to write it? I finished it, and we had a table read.

And I applied that show to the Polyphone Festival, run by the University of the Arts [in Philadelphia]. [The University] shut down last year, but it was a festival where they selected shows to workshop with their students. And I did another workshop with Illinois State. That one actually changed the trajectory of that piece. When I wrote the book—I mean, as you can tell, English is my second language—I wrote the dialogues in Thai and English. It’s a memory play in a way—what happened in 2017, when everyone thought I was the happiest person, but I was struggling so much and didn’t tell anyone. The show has four characters. The professor at Illinois State—he’s from Korea and an immigrant—managed to find two Thai actors in the middle of nowhere. And he did subtitles. So when those two characters speak, they speak in Thai, and that opened my eyes.

How did it open your eyes exactly?

Whenever I wanted to write in English, I always felt like my English was not good enough. There was one time I wrote a short play, and the director actually pointed out that my English was not good enough. And it’s true. But it shied me away from writing. But to see someone who really cared about the work…I live in two worlds. Every day I check news in both Thai and English. And sometimes it’s nice for people to listen to a foreign language and read the subtitles. I never thought that could happen, but it happened

Why did you decide to stay in America? Is it [because of] opportunity? Is it because you’re so sure that if you want to work in musical theater, this is exactly where you need to be?

It’s so weird. It’s just that I don’t like New York.

Do you like the theater scene there?

I do like the theater scene there, but I don’t like the city. It’s so crowded. I used to live in Boston, and Boston is nice and quiet. I think the first time I went to New York I took the bus and landed in Chinatown, and I was like, Oh my gosh! This might sound weird, but I feel like by being in New York, the theater scene makes me a better theater writer. I get to work with the best artists in the world. People in New York are talented. By working with them, collaborating with them, you become a better artist.

But then your work has gone everywhere in the US, right? Seattle, Philly…

Regional theater is another world that I like. And that gives me freedom to travel, too […] Most of the grants require you to do something in that region. Isabella got two grants last year: the Minnesota State Arts Board and the Coalition of Asian American Leaders, and that’s why I traveled to Minnesota three times to do our show.

How’s the theater there?

It’s amazing.

Where in Minnesota?

In Twin Cities. Theater Mu. One of the largest Asian-American theater is there. And to be honest, the local talents are very, very talented. Those are the people who didn’t decide to come to New York.

What are their reasons usually?

Honestly, this is so weird to say out loud, but Minnesota has so many grants, as many as New York. Last year I got the McKnight Foundation Visiting Composer Residencies grant, so I’m required until January next year to spend four weeks in Minnesota. And also, Isabella and I were part of the Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship from 2023 to 2025. We’re finishing that one off. And for some reason, Minnesota grants sometimes require you to be residents of Minnesota or New York.

Did all these grants and working in these different parts of the US change the way you look at the theater scene in New York?

A little bit. I guess it depends on what grant you get. Sometimes if you apply as an individual artist, you get less. I’ve never done a non-profit yet. Maybe I’ll do it soon. This is the difference between the US and Thailand. There are a lot of grants in the US.

When the theater reopened, do you remember what the atmosphere was like in New York?

It felt like everyone was missing theater. There were a lot of comps in 2021 actually. They offered comps for people to come back to the theater. There were shows opening up. It didn’t feel like a normal season [yet]. It felt like a normal season in 2022.

Do you remember the first show you went back to see?

It was on Broadway—Pass Over. People were screaming when there was an announcement saying “Welcome back to theater!” Then I got comp for the Tony Awards ceremony. It was interesting. It was joyful, but I didn’t realize it was going to be four hours long. So that was a long ceremony. I’m an introvert, so I felt I would have enjoyed it more without a comp, just seeing it on TV. Both Pass Over and Tony Awards ceremony were still checking your vaccination cards.

I remember there was a spate of violence against Asian [people in America]. Were you there at that time? I remember it was after Covid. The economy was bad. Many businesses were forced to close.

Yeah, I was there. I went back in spring ’21. A lot of incidents happened during that time. Everyone told me to be careful. Back then, I had to get a Covid test before I flew back to New York. Even my doctor in Thailand was saying to me to be careful. But the thing is I live in Queens. That’s where we have Little Thailand Way, a tiny street in Queens, where a lot of good Thai restaurants are. So I think there’s something about being in Queens, where we were just like, Yeah, we’re all here. Everything was fine. The thing is there’s always some incident in the subway.

Was it worse during Covid? Is it better now? Or there are peaks and valleys?

Maybe because I’ve lived there for a long time, it felt normal. I just feel like, OK, maybe I should be more careful. But nothing really happened, at least for me. The scariest thing that happened to me was a fire. I was in a tunnel between Queens and Manhattan […] I feel there are always stories about the subway. But so far, physically, I’ve never been attacked. Everyone tells me to be extra careful.

Could you describe what the post-Covid New York theater scene is like? Do you feel a change?

I feel like for commercial theater, new works are still processing. I feel I’ve witnessed more work that should have a little bit more life on Broadway but didn’t get that chance. Sometimes I blame it on marketing. Did you know that there was a K-pop musical? It [KPOP] was actually written by two of my classmates. It’s a new work. It [started as] an off-Broadway show in 2017, and then they developed it and made it to Broadway, where it didn’t last more than a month. Because I had to see every show [as a Tony voter], I went there right after they announced their closing. They were trying to do a “Save K-pop” campaign, but it didn’t happen. I feel like [it’s hard] for new works that aren’t adaptations of a movie or a novel. I mean it’s already been hard to do that commercially, but to witness a show that two of my classmates had worked on for a long time close was kind of sad.

What does this mean for new works? Do you think people take less risk especially after Covid because a lot of people weren’t able to work at all for quite a long time?

I think for commercial theater it’s quite different because it’s all about making money, making sure that they recoup. I mean there was an article about it, too, that theater has become more expensive. And certain shows take almost a million dollars to run per week. So I feel like new works are different. When it isn’t an adaptation of something that [people already] know, it takes more risk. There might be more opportunities in [non-commercial theater], but also non-profit. I feel like after the pandemic, during the pandemic, and maybe in 2021, the theater scene, even though we were on Zoom, was still flourishing in a way. But since then, you started getting emails and newsletters from friends saying, “I was supposed to have a show, but it got cancelled.” I guess, financially, it’s a little bit harder for all the regional theaters. Some of them are closing, some of them are merging. It’s a strange time.

Where were you creatively after Covid?

I continued to be busy. Sometimes I don’t think like that, but I guess I’m the lucky one in a way. So after [Dear Mr. C], it felt like a discovery: Oh, I guess I can do something. Maybe not as perfectly as someone who speaks English as their first language, but…Last year, I was part of the fellowship at the New Victory Theater, a TYA [theater for young audiences] company in New York City. I proposed that I was going to do an adaptation of the Sudsakorn story [from Thai epic poem Phra Aphaimanee] as a play with music. But once I got [the fellowship] and started writing the outline, I found out that actually it worked better as a musical. And I’m the kind of person who likes deadlines. The fellowship started in September 2023 and ended in June 2024, so I thought, I had 10 months. I can write a song per month. That sounds great. But then they told me that I had a presentation in April. But I liked that because it actually pushed me to do more. So by February last year, I finished The Adventures of Sky and Friends. And that was the first time I wrote lyrics. I feel like the pandemic actually made me explore things more in theater.

Because you constantly had to meet new challenges or because you had time? You didn’t seem to have had time.

I just all of a sudden started to do something outside of my comfort zone. But on the other hand, because I’m a composer, it’s not easy. It’s actually easier for me to think of the lyrics because I think of the melody. And then it’s like a jigsaw puzzle. So I wrote the TYA musical, The Adventures of Sky and Friends, set in Queens. This Thai girl, Sky, who moved to the US, goes on an adventure in her Queens neighborhood and finds friends, like Sudsakorn finds the dragon horse. It was fun. It was really fun. And then I just finished a residency at the Museum of Chinese in America […] I proposed to interview Thai people about Thai food. It became With Rice, a documentary musical […] I always apply to all these things. And I’m always like, Well, if I get it, I’m going to write it.

How do you feel about this artist life that is so much about grant writing? Is that just the reality for a young, new, not-yet-established artist in America?

In a way, yes, unless you’re really rich, then you can produce your own show. Great, amazing, but for me, I like applying to things. Sometimes you also get to travel. You get to meet new people. You get to go to cities that you’ve never been before, making new friends while staying there. Sometimes, you dare to do things that you’ve never done before, like I wrote my first full-length musical. That was crazy. I mean, it was verbatim in a way, too, because I just interviewed people and used that as the book part. I started that residency in October last year, but I came back to Thailand. It was great, too. I got to meet all the Thai people. I went back in November to interview more people. December and January, I wrote it, and I presented in February. So I wrote everything in two months. Not perfect, but it was a big first.

What has surprised you the most about yourself?

That I can do more than I expected. I’d never thought I would write lyrics. I still don’t consider myself a librettist. I mean, librettist maybe, yes, but not a lyricist. I feel like, if you step out of your comfort zone, you’ll discover more things. Here’s the thing, I feel like musical theater is such a world that a lot of magic happens in the room when you have your collaborators. That’s always the case, and I love to do that. However, the composer is the last person to deal with everything. Sometimes you can write the music first, then the lyrics come in. But the last person to deal with the score is the composer. The lyrics are set, the book is ready, then it’s me who has to go back to the score again to make sure everything is aligned: the lyrics are correct, the dialogues are in the right place. I’m always going to be the last person to deal with everything. And it’s nice. Something that’s different between musicals and operas is, in operas, you’re in trouble if you can’t sing it. But in musicals, I’m in trouble if they can’t sing it. I feel like my life has always been about waiting. That’s what I’ve been training for. I’m used to be a waiting person, but it’s nice that I can have projects that I’m in control of everything. Sometimes it’s nice to balance between waiting and being in control.

When I interviewed you and Isabella in 2020, the two of you had been busy with “Half the Sky”. There’s been a lot of workshops and development and readings and mini concerts. Where do you want it to be?

Ideally, it’s to have a production. We’re kind of focusing on another project this year. It’s called Sunwatcher. That one felt like I’m getting another master’s degree in music composition.

Oh, how come? You’ve been working on this even before the pandemic?

During the pandemic, actually. It’s a story about a Japanese scientist, Hisako Koyama, who lived in Japan during World War II and drew sunspots every year for 40 years. So as a composer, I feel like it’s my task to tell the audience who we are, where we are in the piece. There are four types of music I need to write. One is the time period that we were in, which was the 1940s. There’s music for a character, Amaterasu, who’s the sun goddess, so for that we incorporate the taiko drumming and a more traditional Japanese score. I play the fue [Japanese bamboo flute] for the show. Then, there’s the music of Hisako Koyama, which we want to sound different from everyone else, so I kind of make her sound more like musical theater, but J-pop. And then there’s the music of the sun. We were trying to figure it out, and we were like, “What about looping?” So we ended up using two looping machines. One with the vocalist. Isabella was doing that. And one keyboard, which is me. So with just two people, we can create the whole orchestra.

We did Joe’s Pub in 2022 for Half the Sky, but since 2023/2024, we’ve been focusing on Sunwatcher. It felt like learning a new instrument. This tiny thing that we bought. The instructions never really helped. It was more like, “Just hit the record button and try.” We went to a summer residency to just do that: hit the record button—"What are we doing? Look at the instructions. Does it help? Let’s try it again.” So 2023/2024, that’s when we got two grants in Minnesota. And that’s why we went there last year three times. We workshopped the piece with taiko drummers. And we did a reading last year. It felt like for the last two years we were focusing on things we had never really done before.

For Half the Sky, we went to Nepal in 2022 for two weeks. We bought a lot of instruments back. We had a small grant, but we were kind of like, “Let’s just go.” It was a twist of luck because I went to a hospital in Thailand to get some shots before traveling. And the doctor was like, “I just went to Nepal, and there is a guy who is Nepali, but he lived in Thailand for 10 years. He can speak Thai fluently.” And he took us around Kathmandu. There was a jazz conservatory where some of the students were amazing traditional Nepali musicians. So we took some classes. We bought some instruments back to the US. For Half the Sky, again this is me being a composer, I feel I need to write music that tells people where we are in the piece. I would love to go back to Nepal again. Another thing that we need to try to do is a movement workshop for the actors. I feel like there’s a lot of movement happening in the piece because everyone is climbing.

Maybe climbing lessons?

There was a UK show actually that is about climbing. The first day of rehearsals they went to a climbing lesson together. Maybe. We’ll probably try to get a residency to something maybe this year or next. I also want to go back to Nepal to do meditation retreats.

Do you feel that there’s a lot of room for musicals like this that’s more experimental musically? If they become full-scale productions, where do you envision them being staged?

For Sunwatcher, I feel it can be anywhere. It can be outside. It can be anything. It can be in a museum. Every show is different. Half the Sky feels like the most traditional theater piece. But also from the get go, we felt like it doesn’t have to be. I feel like our writing is flexible. The show that I wrote about my mom, Dear Mr. C, has only four actors. Broadway isn’t my goal. If it happens, great. If not…I feel like theater can be flexible. And maybe that’s something that I learned during the pandemic, too, that theater can be flexible. It can be anything that isn’t just hundreds-seat theaters. There’s so much room for me to explore my potential, once you feel like you don’t need to be on Broadway.

You think that’s what everyone thought when they were studying musical theater?

I think a lot of people thought about it. For some reason, it wasn’t really my goal. I feel like whatever I’m writing is not the typical stuff people are writing. Maybe this sounds selfish, but I like to write about things that I care about. And so far, everything that I’ve worked on, I feel very happy about. And maybe I’m one of the lucky ones who can say that. Or maybe because I don’t trap myself into the word “Broadway”. So whatever I’m writing, I want to become a better artist. If I learn something, I’m already happy. I’m not a rich person. Whatever I’m doing, I’ve learned something. It’s not a struggle. I don’t need this financially.

So you don’t identify as a struggling artist in New York?

I guess I don’t. There are times where I’m like, “Dammit, I didn’t get this [grant]!” There’s always that. But so far, I’m very happy with what I’m doing. And so far, I’m very proud of what I’m doing.

You were in both Thailand the US during the lockdowns…

I spent so many nights not sleeping because of all those rehearsals. But it was still always nice, even though I was not sleeping. I got to see my sister before she was going to work. My mom made breakfast. It’s interesting because I had a conversation with someone the other day. You know, during the pandemic, there was a trend with Thai people emigrating somewhere else.

Well, New Yorkers left. A lot of people left big cities, right?

Yai pratet [moving countries]. That was the trend. Even now people talk about it. I have a different opinion. I’ve had a different life. One of the awards that I received was because a person passed away, my mentor. One of my mentors that I had after I got out of college passed away in 2017. Months before his passing, we were still corresponding. He wrote my recommendation letter and stuff. My mom is getting older. As my mom dropped me off to take the bus to Bangkok this morning, we talked about it. I don’t think she should travel to New York that frequently anymore. I feel like my life is different from everyone else in Thailand who wanted to migrate. I feel like I just want to find time that I can work, but I also want to spend time with my family.

Do you still feel a kind of hangover from whatever happened during Covid?

One thing about theater that didn’t happen before was that, before, you needed to be present in that room. And that had always been the definition of theater. I think the pandemic really taught us that you really didn’t have to be. I know it might not be the most ideal situation. And of course, we need to be in the same room to finalize things. Before the pandemic, I said no to traveling back and forth a lot because I was like, “I can’t. I need to be here.” But nowadays, I can. We’ll just figure out. It’s going to be fine. It’s not perfect, but I can do it.

Do you feel torn about these two places now?

A little bit more, especially last year. I didn’t realize that as I get older, everyone else is getting older, too. My grandmother was hospitalized five times last year. And one time this year already. It’s interesting because I started recording her voice. That’s something I had never done before. They were not secrets. They were things I never thought about.

I actually just went to the death railway in Kanchanaburi. And I’m writing a play called KHAM (Crossing) about it, too. Two of my distant relatives were part of the railway construction, but they never returned. It was interesting hearing those stories. As we get older, everyone else is also getting older. I’m happy to be in the musical theater world and the theater world in general. I’m happy that every project that I’m doing, I feel like I’m improving myself. I get to meet amazing people. I get to meet amazing institutions. I get to collaborate with a lot of people. But at the same time, I’m also happy that I get to spend time with my family, that I prioritize personal life more than just run, run, run. I feel now I have more choice to say no, or to say that I’ll deal with it. As a theater person, you’re always taught to say yes. And I said yes so many times. And I think the pandemic made me start to say, “Yes, and…” or even “No.” In a way, I love theater in America, but I’m also curious about theater here. So hopefully, I’ll start to explore that more […] The chance to be home is always a blessing.